Making of Orozco: Man of Fire

“Not only is the story fascinating, the film looks gorgeous. All fine arts films need to rise to this visual standard!”

By Laurie Coyle, Co-Producer/Director

Originally published in VOZ Magazine, Summer 2007

It was 5 AM when the flight attendant announced our descent. Through the airplane window, I could make out the faint glow of daybreak to the east. We were on Mexicana Airline’s “tecolote” flight—the “red eye” from San Francisco to Guadalajara. There were no tourists on board; instead, Mexican immigrants going home to visit their families. As the plane approached, ‘canned’ versions of Mexican standards played over the intercom. When Guadalajara, Guadalajara came on, a man in the back of the plane burst into song. Other passengers let it rip with whoops and whistles, crying out “es bueno ser mexicano, que no?!” By the time we got off the plane and through customs, the terminal was packed with anxious onlookers waiting for their loved ones, who were hauling enormous suitcases and boxes overloaded with gifts.

We were excited too: after three years of fundraising and preproduction for a documentary portrait of the Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco, we were finally in production. We’d heard, “You want to do what?” from North Americans who’d never heard of Orozco, Mexicans who considered him passé, and crews wondering why we wanted to hike up a mountain to film a volcano, or how we could hang neutral density gels a hundred feet above the ground. But incredulity had given way to support, and we were poised to begin two grueling weeks of shooting in some of Mexico’s largest and most important public buildings.

Like any film production, OROZCO: Man of Fire was a journey. Why Orozco? What inspired us to make a film about an artist who had been dead for over half a century? On a research trip to Mexico, we scoured bookstores for sources but the results were disheartening: the average art section carried five titles about David Alfaro Siqueiros, ten on Diego Rivera, and even more about the recently idolized Frida Kahlo (selling a large selection of chácharas like clay Frida figurines). As for books about Orozco, we usually found none at all. But piecing his life together from out-of-print books, conversations with people who had known him, and his own writings, we discovered an extraordinary individual with an ambitious and humane vision of the role of art in society.

In making OROZCO: Man of Fire, there were times we felt we were retracing the artist’s steps, fighting an uphill battle for recognition, convincing broadcasters that Orozco was not too obscure or foreign for public television. When we started out, the environment was rather “chilly” with PBS under intense government scrutiny and calls for “blockbuster” programs with mainstream appeal that could attract more corporate underwriting.

Public funders embraced the project and provided 98% of our funding. Our first grant came from the National Endowment for the Humanities, who would become our largest underwriter. Our first production dollars came from Latino Public Broadcasting, (LPB) with funds from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. They were our second largest funder. We also received support from the National Endowment for the Arts and The Independent Television Service (ITVS). Artist biographies are a hard sell to private foundations, but we did receive small grants from Brown Foundation, LEF Foundation, Nion McEvoy and Nu Lambda Trust.

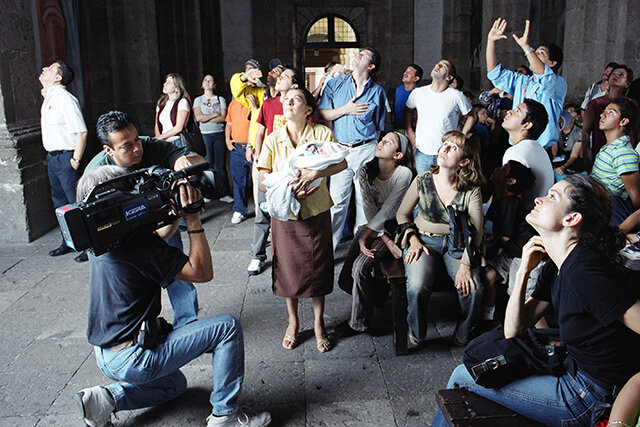

KERA Dallas came on board as our co-producer and provided High Definition equipment that would have been unaffordable otherwise. We wanted the viewer to have the experience of being in the presence of a great work of art, so we shot in wide screen format with moving crane and dolly shots to envelope the viewer in the world of the murals. DP Vicente Franco’s camerawork included use of a jib crane, dolly, tracks and stedi-cam to capture the three-dimensional quality of these huge public buildings. It was the first time Rick Tejada-Flores and I had worked with such large lighting and grip crews of nearly twenty people.

Organizing a bi-national (U.S.-Mexico) shoot of murals located in Mexico’s most important public buildings required the active cooperation of countless institutions and individuals, beginning with the Mexican government. There were multiple levels of permits and, like a feature film, coordination of large numbers of people. One time location scouting at the Supreme Court in Mexico City, we were lying on the floor trying to “frame up” a low angle shot of a mural. An elegant gentleman approached and asked in English what we were doing. He chatted amiably with us, and wrote his name on a slip of paper. We later found out he was a justice of the Supreme Court, and he became instrumental in convincing the Court to grant us permission to film, which we did in the middle of the night when they were not in session.

At the other end of the shooting spectrum was the intimacy of the interviews with the elderly artists and Orozco family members. Will Barnet, Elizabeth Catlett, Arturo Garcia Bustos, Gobin Stair and John Wilson (all between the ages of 76 and 96) shared their wisdom of a whole lifetime spent creating art. Their spirit and spunk inspired our work and gave us a more personal connection to Orozco.

We didn’t want to make a conventional bio-pic, and were blessed to work with talented people who helped us make a film that would do justice to Orozco’s passion and irreverent humor. After much searching, we met visual effects artist Robert Conner, who created whimsical visual tableaux. Our composer David Conte’s orchestral score gave the documentary the majestic sweep Orozco’s murals needed. Our editor Ken Schneider brought a masterful hand to structuring an unwieldy script into compelling narrative. When we chose Damian Alcazar to do Orozco’s voice over, we were unaware he had won almost every major acting award in Latin America that year. We hired him because he brought great depth and dimension to how he read the lines. And when Anjelica Huston agreed to be our narrator, we had no idea she was married to the famous Mexican sculptor Robert Graham. We just felt she had the right touch for Orozco’s irony and was the perfect muse. As they say in the book business, we thank them for their contributions—the program’s limitations are ours alone.

The public broadcast climate has really shifted since we started our journey with Orozco. There’s much more a spirit of renewal, embracing diversity. OROZCO: Man of Fire presents the human drama of one artist’s struggle for recognition. It is also a story of cultural exchange between two peoples in which Orozco and his fellow muralists were trailblazers. With the birth of a new civil rights movement headed by Mexican immigrants, there’s an urgent need to create awareness of the contributions of Mexicans to American society. In making this film, we hope we have succeeded in drawing attention to a significant, overlooked chapter in American culture. Orozco is indeed an American Master and we are pleased that he has found his rightful place.